Kava: A Story of Misinformation and Resilience (Part 1/3)

Published in The Fiji Times on March 12, 2024

This series details kava's rise, economic impacts, and recent positive developments as it continues to gain popularity worldwide, overcoming stigma and misinformation.

A History of Kava

Back in 1997, an expert in kava, Dr. Vincent Lebot, predicted that consumption of the Pacific Island beverage would become a global phenomenon. Today, more than a quarter of a century later, his words seem prophetic. The relaxing, non-addictive beverage, derived from the roots of a leafy crop, is widely consumed in the Pacifics and is gaining popularity globally. Kava is available at more than 400 kava bars across the US, providing a healthy social alternative to alcohol. Millions also take it daily as herbal supplements which offer relief from occasional anxiety, amongst other benefits.

Kava is believed to have originated in the north of Vanuatu at least 1,500 years ago.

Kava is believed to have originated in the north of Vanuatu. It was first consumed at least 1,500 years ago, and some of the first seafarers are later thought to have spread it across Oceania. Traditionally, the bitter plant roots are processed, and the resultant powder is prepared with cold water to produce a calming beverage. The consumption of kava has long been integral to Pacific cultural practices, used both for ceremonial occasions and as the centerpiece of gatherings in Vanuatu, Fiji, Samoa, and Tonga. Still today, large swaths of those countries’ populations drink it daily, and its consumption brings communities together peacefully.

Kava’s Journey to the US

Over the past 130 years, kava made its way across the globe. From the late 19th century on, kava became increasingly popular in Europe and the US as a remedy for conditions as diverse as urinary tract infections, kidney issues, and sexually transmitted diseases. Decades later, it started to be used to ease occasional stress and anxiety. In the early 2000s, bars and lounges began to open in the US, first in Florida and then in New York. They often serve the beverage in a hollowed-out coconut shell, in its traditional, undiluted, and unadulterated form. It has a mouth-numbing effect and swiftly relaxes the muscles with a licorice-flavored hint.

In the early 2000s, bars and lounges began to open in the US, first in Florida and then in New York.

However, by the turn of the millennium, an estimated 70 million kava doses, in tablet form, were being prescribed daily by European doctors. Accordingly, there were commercial incentives behind the decision of several companies to implement new chemical methods to retain more of kava’s active ingredients, the kavalactones. In 1995, a European company started using a new method with a manufactured chemical, acetone, to extract the kavalactones.

A Crisis and Regulatory Response

In 1999, reports of adverse effects on consumers' livers began to emerge when as many as 30 people were hospitalized after ingesting products, including ingredients extracted from kava. Some suffered liver failure, others had hepatitis and jaundice. A retrospective trawl of adverse event reports identified a total of 93 cases around the world linking kava to liver issues. Eleven people required transplants, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and there were also disputed reports of a handful of deaths.

The headlines were damning – and a far cry from reporting just months before, which lauded how kava pills provide calm without rendering their consumers “dull, sleepy or addicted” like some pharmaceutical drugs. The mood music had taken an about turn. “New Questions About Kava's Safety,” “Seeking to Fight Fat, She Lost Her Liver,” “FDA Warns That Kava Use May Cause Liver Damage.” Crucially, however, the links remained tenuous and certainly not causal.

In the early 2000s, after decades of mass use in the Western world, kava was ousted from the supplement market in almost the blink of an eye.

The regulatory response to restrict the exotic, foreign, little-understood plant – at the time, the ninth most popular herbal supplement in the US, worth $68m (USD) per year in sales – was nonetheless swift. Germany warned it would ban the plant in all its forms, soon making good on the threat. Switzerland withdrew kava from the market. The UK requested manufacturers pull products prior to an eventual formal ban. France completely banned its sale, despite for decades providing a kava-based antiseptic, “Kaviase,” for free through a national health scheme, without any detected side effects. Then, in November 2001, European regulators restricted the sale of kava products across the entire continent. Health authorities elsewhere followed suit. Australia effectively banned kava entirely in 2007. (It only recently opened the door to commercial imports under a special pilot program).

After decades of mass use in the Western world, kava was ousted from the supplement market in almost the blink of an eye, even while it was gaining popularity and providing a far safer alternative to pharmaceuticals, which can have serious side effects. The industry was disorganized and struggled to muster an effective collective response, but kava still had many defenders. An authoritative 2002 Cochrane Collaboration review of kava research analyzed the results of 12 double-blind randomized controlled trials. It found that: “Adverse events as reported in the reviewed trials were mild, transient, and infrequent.” The gold-standard medical analysis noted that kava extract was effective and seemingly “relatively safe for short‐term treatment” of anxiety, though more detailed data were required.

Experts Weigh in on Kava: A Big Pharma Connection?

Edzard Ernst, then emeritus professor of complementary medicine at the University of Exeter, co-wrote the Cochrane review. “That kava is indeed effective is not in doubt,” he said in 2004. “As for its safety, the German cases looked rather dodgy and may in fact be politically motivated.” This raised the possibility of influence from Germany’s powerful pharmaceutical industry, which may consider the natural remedy market as an existential and looming threat. “Compared to the health risks associated with conventional benzodiazepines, kava seems safer and, on balance, better. In my view, there is no doubt that kava is preferable,” Ernst added. “If taken correctly, there is very little risk.”

Additionally, an academic review of the history of kava consumption reported that “Prior to the mid-1990s, there was not a single report of liver toxicity from anywhere in the world.” Dr Lebot, coauthor of Kava: The Pacific Elixir, says kava has been safely used in the Pacific for centuries. “Any potentially toxic effect would be very easy to detect statistically, and none has been observed.” Surveys of Aboriginal communities in Australia, where kava is routinely consumed, have observed no signs of long-term liver damage.

“During my early research, I never used acetone to extract kavalactones, and I was surprised that companies used it,” says Dr Lebot. “They explained to me, face-to-face, that it was the most ‘efficient’ available solvent to extract the maximum of ‘soluble solids’ to produce their extract.” However, company officials told him they knew that acetone was extracting much more than kavalactones, and especially all flavokavains, which characterize poor kava varieties. Later, the businesses appeared to acknowledge the mistake. “In the new patent they developed for the ‘boom’ in the US, they controlled the level of flavokavains to solve this ‘technical problem’,” Dr. Lebot adds.

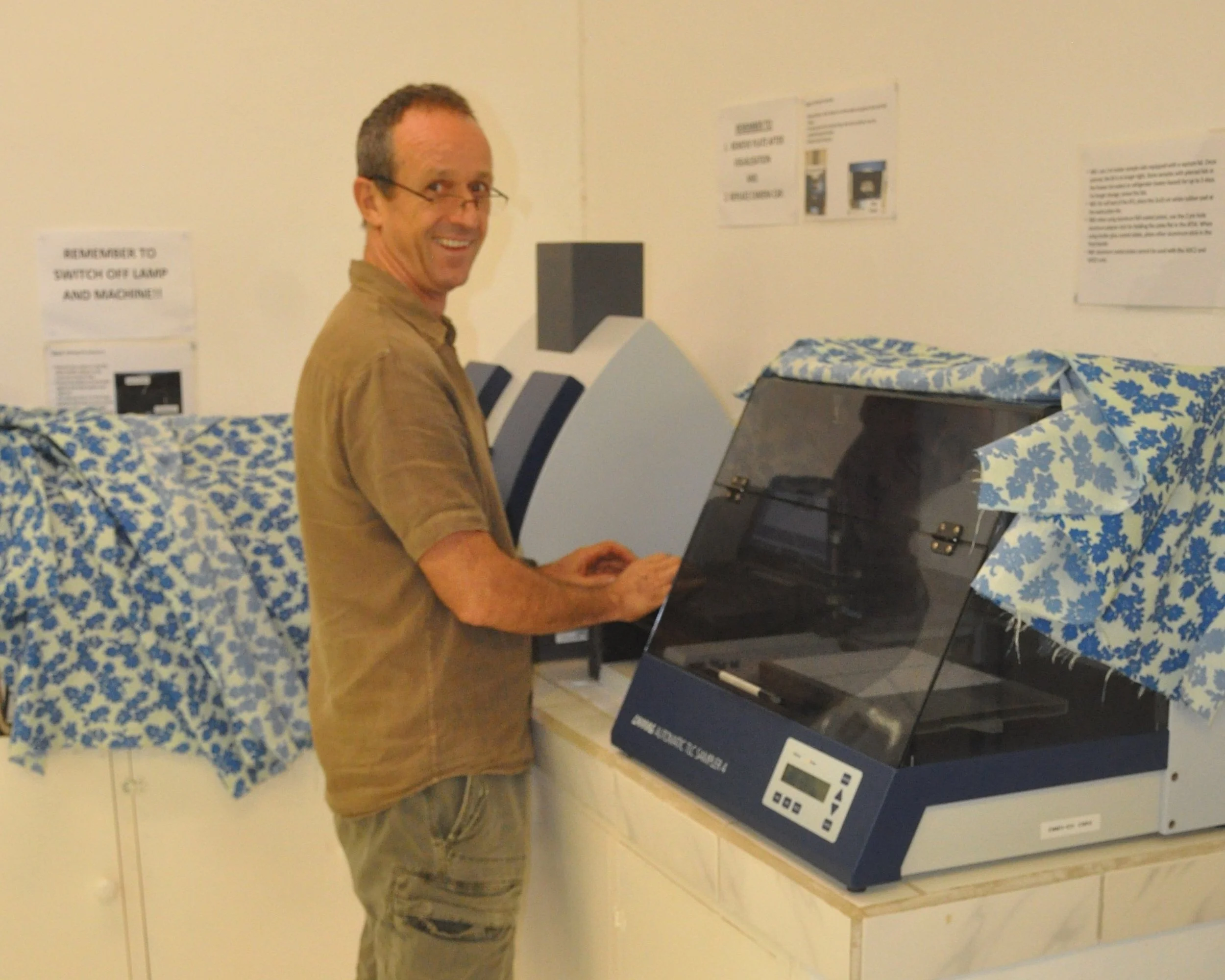

Dr. Vincent Lebot, kava expert, researcher, and author

Reviews of the liver toxicity cases by German and European authorities have largely failed to draw a causative link between the kava extracts and the harms. An official letter from the German regulator later revealed that its decision was also due to the absence of evidence proving the efficacy of kava rather than concerns around its safety, as no formal large-scale clinical safety trials had been undertaken before its use as an herbal supplement exploded. At the time of the incidents, most people affected were taking pharmaceutical drugs known to be toxic to the liver. Subsequent investigations also revealed, several were also elderly heavy drinkers. It is also possible that acetonic kava extracts are contraindicated with certain pharmaceutical drugs.

Complicated Kava Cases Found to Be Rare

A subsequent independent analysis of the case reports only found a certain link between one of the cases and kava. In that event, the individual had consumed many times the maximum recommended serving in Germany. A World Health Organization report concluded that in eight of the cases, there was a “probable” association between liver disease and kava use. The causes of the other cases remained unclear or were debunked. In any case, they were largely restricted to individuals who had consumed the acetonic extract products made in Germany.

The WHO report later said kavalactones “may rarely cause hepatic adverse reactions because of kava-drug interactions, excessive alcohol intake, metabolic or immune-mediated idiosyncrasy, excessive dose, or preexisting liver disease.” It continued: “Products made from acetonic or ethanolic extracts appear to be hepatotoxic on rare occasions, seemingly from non-kavalactone constituents.”

A 2019 paper in the journal Drug Science reported that the incident rate of liver toxicity due to kava is one in 60–125 million patients. “Only a fraction of the handful of cases reviewed for liver toxicity could be, with any certainty, linked to kava consumption, and most of those involved the co-ingestion of other medications/supplements,” it added.

As millions of consumers purchase and consume kava every day around the world and have done so to varying degrees for centuries, coupled with a canon of scientific research, it seems clear that kava presents a minimal risk to consumers. However, despite the evidence that kava is a natural ingredient that stands to benefit millions of people, it is still viewed with trepidation by many as it works to overcome the past. It is up to the scientific community, regulators, processors, advocates, and critics to work together to examine the facts and establish a fair judgment on kava.